Buster Keaton's 'favorite place on Earth' --

Muskegon -- hosts film festival

by

Neal

Rubin || The Detroit News

by

Neal

Rubin || The Detroit News

September 24, 2012

If the loggers around Muskegon hadn't been

so fundamentally stupid a century ago, there

would be no Buster Keaton convention there

next month.

It's funny how history works sometimes —

though not as funny as Keaton.

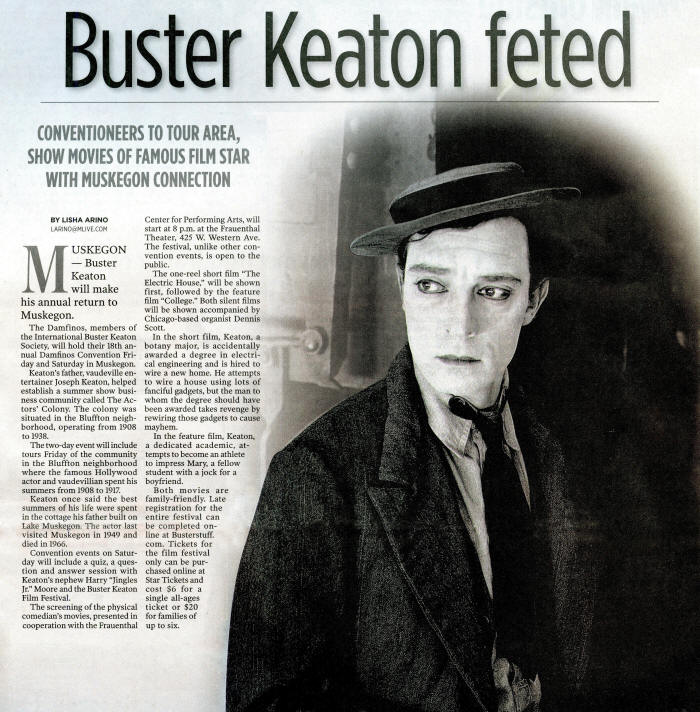

Joseph Frank "Buster" Keaton was born Oct.

4, 1895, and started in vaudeville at age 3

or 4, getting booted across the stage by his

dad. (Apparently, you had to be there.) He

went on to do truly hilarious things in

silent movies, talkies and television, a

rare series of transitions that still leaves

him pretty much forgotten today.

Over time, he's gone from "ask your mother"

to "ask your grandmother" to "I dunno, look

him up on Google." But if you can track his

movies down, or catch a few clips on

YouTube, you'll find that they're still

brilliant — and if you venture to the 18th

annual Buster Keaton Film Festival and

Convention Oct. 5-6, you can see his work on

the big screen just the way Grandma did.

Unless it was somebody older than grandma.

Keaton once wrote that "The best summers of

my life were spent in the cottage Pop had

built on Lake Muskegon in 1908." His widow,

Eleanor, said Muskegon was "his favorite

place on Earth." And that's where logging

comes in.

By the 1880s, 47 sawmills bordered Muskegon

Lake, and the city was known as the Lumber

Queen of the World. By 1900, the industry

had just about disappeared, because the

damned fools cut down all the trees.

Therefore, says local historian Ron Pesch,

when Keaton's dad passed through the city on

tour, there were cleared lots available

cheap between Lake Michigan and Muskegon

Lake. Vaudevillians had summers off —

theaters weren't air-conditioned back then —

and Joe Keaton told all his friends to come

on up.

Actors' Colony came, went

Joe Keaton wasn't the first performer to buy

a lot, but he was the most insistent. By

1911, more than 200 entertainers lived at

what became known as the Actors' Colony.

Residents included some of vaudeville's

biggest names, and also an elephant and a

zebra from Max Gruber's "Oddities of the

Jungle" act. The humans would fish, boat,

drink, practice, play pinochle and put on

season-ending shows for the locals. The

elephant would sometimes carry drunks home

from the tavern.

Like zebras, alas, time does not stand

still, and the entertainment industry

changed. Buster Keaton moved to New York and

then Hollywood, creating and directing

increasingly inventive deadpan slapstick and

becoming known as the Great Stone Face.

By the late 1930s, the colony was gone. By

1966, so was Keaton; lung cancer took him at

age 70. But when a cadre of zealots formed

the International Buster Keaton Society two

decades ago, they decided on his favorite

city as the place to gather.

Muskegon might not be the most convenient

spot, but Pesch has met Keaton fans there

from Germany and New Zealand.

Dinner and a movie

This year, the revelers will tour the colony

site, play baseball on Keaton's childhood

field, hear from Keaton experts, dress in

their 1920s finest for Saturday dinner, and

finally catch a silent movie and a short at

the lovingly restored Frauenthal Theater,

where Chicago-based organist Dennis Scott is

so good he actually makes the MGM lion roar.

The movies are open to the public for a

trifling $6. For information, visit

www.silent-movies.com/Damfinos.If

you can't wait two weeks for a Keaton fix,

try Iola, Kan., on Friday and Saturday. The

annual Buster Keaton Celebration there

commemorates his birth, even though he was

born seven miles away in Piqua, a town he

visited exactly once thereafter.

Piqua has a Buster Keaton Museum in the

front room of the water district building,

but it takes a larger metropolis like Iola

to host the actual celebration.

If you appreciate Keaton's genius, multiple

festivals seem entirely appropriate. This

was someone who appeared in vaudeville and

in "Beach Blanket Bingo," claims two stars

on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and had Harry

Houdini for a godfather.

People are resistant nowadays, Pesch

concedes, to the notion of watching silent

movies, especially after he tells them

they're in black and white. But when he can

lure them to the theater and the final

credits roll, they'll stand and cheer.

Loudly.

nrubin@detnews.com

(313) 222-1874

|

|

October 4, 2012 - Muskegon Chronicle |